|

Service in UK 41 Commando Upon my return from Aden in June 1967, my mother and Rose-Marie met me off the train at Lincoln station and almost did not recognise me, I had changed so significantly. That period in any young man’s life is one of great change, but I’d also spent a lot of time working on my suntan prior to my return and looked quite different.

Back in England, I had a well-deserved two-week’s leave. I had kept in contact with some of my friends from the days of the Air Training Corps and we would meet up when I was on leave. So, upon my return, I phoned Phil Johnson and we arranged to meet Martin Codd, a friend of Phil’s. Martin had befriended some trainee teachers from the teacher training college in Lincoln and had fixed us up with dates. At that time, the college was for females only, so they were only too pleased to have some male company. We subsequently developed a brilliant arrangement there, for if we wanted to go out for the evening, we could contact them, and if they weren't able to, they would check with one of the other girls for us. At the end of my leave, I joined my next unit, 41 Commando, in Bickleigh near Plymouth, where I joined F Company, 5 Troop, along with George who had been in Aden with me. We had become good friends, a friendship that was to last all our lives.  F Company, 41 Commando 1968. Nat standing 8th from right, me 9th.

Upon joining my section, I became friends with a guy named Nat Temple. We worked very well together and had similar interests on social nights out.   Nat and me in 1968 and in 2014.

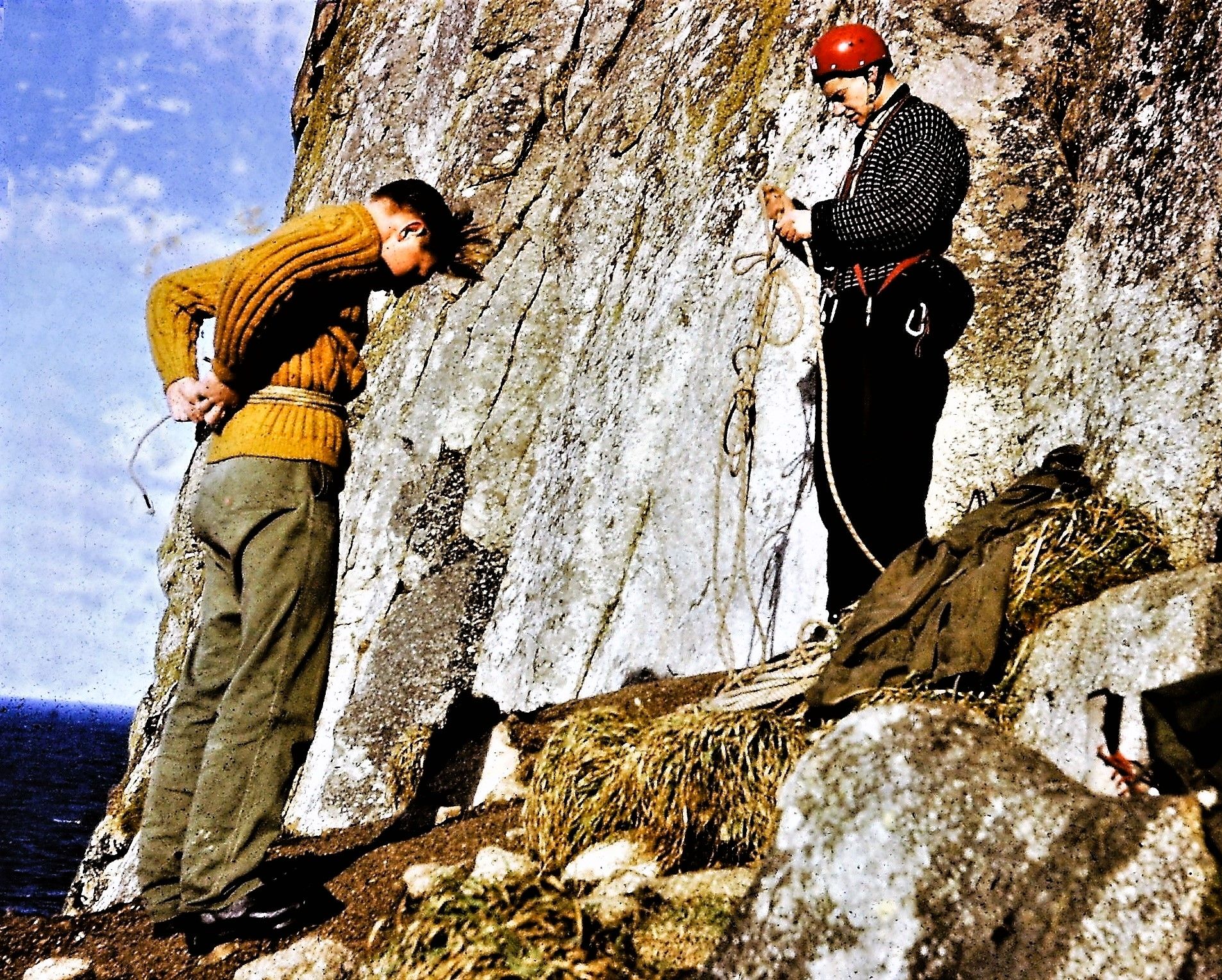

Throughout the summer, we were engaged in training and exercises. Some of the exercises were local while others were in Norfolk and even as far away as Northumberland. On one exercise, our troop was doing a patrol and we were all stretched out in single file. We stopped and waited for what seemed an age. Eventually, the guy at the back wanted to know why we had stopped so, as was common practice, he tapped the guy in front of him on the shoulder and whispered, “Why have we stopped”. This message was passed up the line of twenty guys to the officer at the head of the file. He responded, ”We are consolidating our position” which was passed back one-by-one to the guy at the rear who had asked the question. Upon receiving the reply, he responded up the line with “What does ‘consolidating’ mean?” Many years later, after becoming an officer myself, I always bore that event in mind when talking to people, gearing my vocabulary to their level. Generally, our officers were good. Nat and I even went rock climbing with our troop commander. There wasn’t a “them and us” attitude, which you might get in some arms of the military.  Nat and our troop commander on a climbing trip in Cornwell.

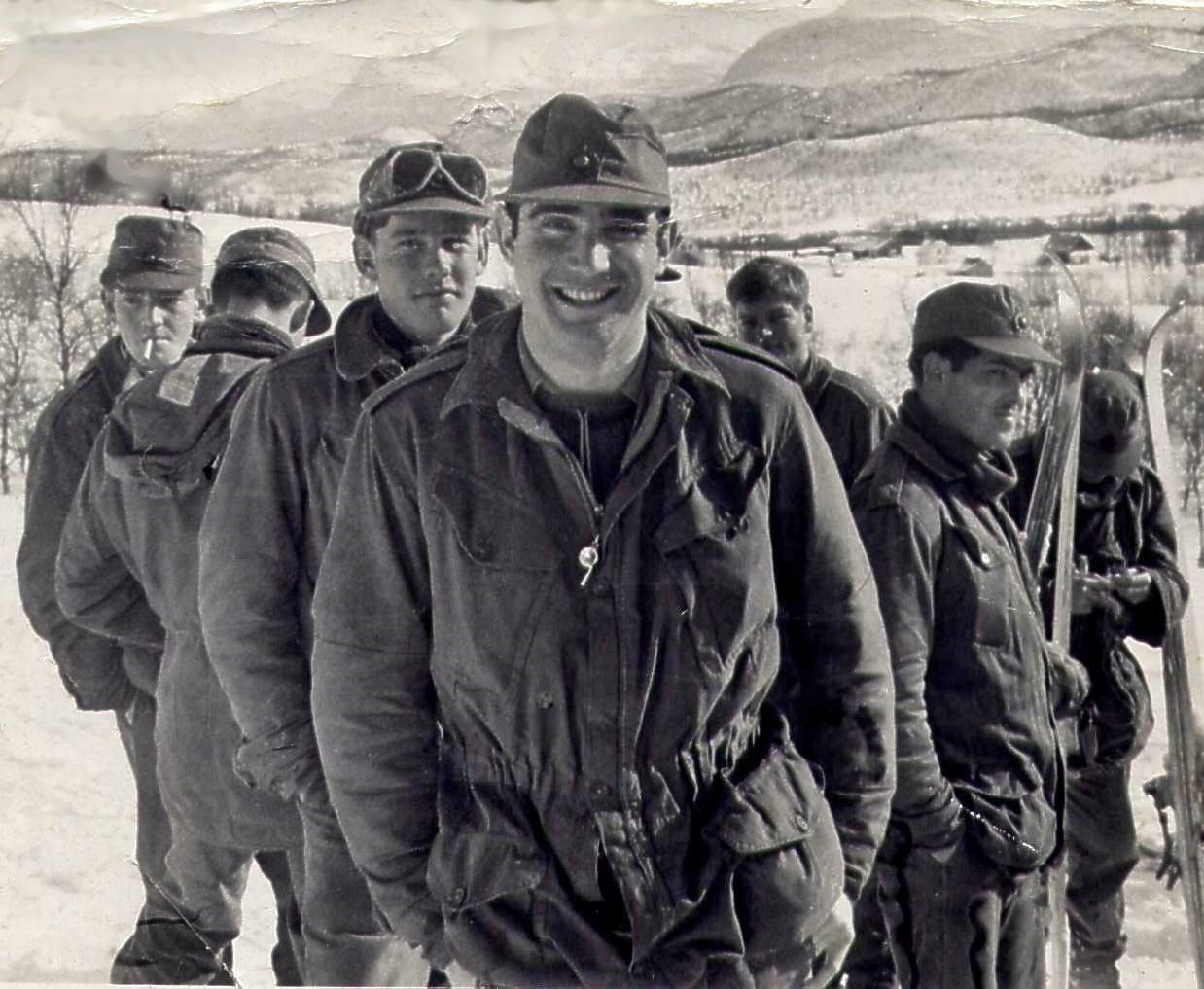

In the autumn, we learned that F Company was earmarked to be on call should the UK be needed to assist in the protection of NATO’s Northern Flank in Norway. That meant we all had to learn to live and fight in cold weather conditions and so began our Snow Warfare Course. It started initially at Bickleigh with six weeks of theory and skiing instruction. We also had to learn about survival in the harsh conditions that we would encounter in Scandinavia, and how to conduct military operations under those conditions. Certainly, our company moving around the camp on skis amused the guys from the other companies. In February 1968 we flew to Norway for a further six weeks to put into practice what we had learnt. We landed at a place called Harstad, which is well above the Arctic Circle. In addition to learning to survive and fight in such conditions, we also had the task of testing equipment to determine its suitability for the Government to purchase for British troops. We soon realised much of the equipment we had was definitely not suitable.  Me with my section in Norway.

While in the field we lived in tents, but we also learnt to construct and live in “snow holes”, which were, in fact, quite comfortable. Snow holes were made by digging into the side of deep snow and then extending the area underneath to form sufficient space for someone to live in. The ceiling and sides would then be sealed with heat to form a frozen barrier. They were quick to construct and quite difficult to spot, giving the inhabitant a good sense of security. Tents on the other hand were a lot easier for the enemy to detect.  Constructing snow holes.

The food in Norway was disappointing, to say the least. We actually looked forward to going out in the field because then we got ration packs, which were more palatable than the food in the Norwegian Army barracks! We pleaded with our families back home to send us food. We felt like prisoners of war looking forward to a Red Cross food parcel. When we returned to Bickleigh from Norway, the Commanding Officer, who had heard of the problems with the food, put on the most wonderful meal for us with steaks and all the trimmings. It certainly made us feel welcomed back. On my return home from Norway, I applied for a Parachute (Para) Course. This was something I had always wanted to do since I had done a simulated parachute jump at an air show when I was 14 years old. When I applied for the course, I had an interview with the Company Commander, who would either approve or reject my application. I told him that, when I entered the military, I was torn between joining the Parachute Regiment or the Marines but when I found out the Marines did parachuting, I decided to join them. He readily approved my application. George was also on the same Para Course. It was nice having the company of a friend. That’s one of the great things about the Marines: it’s very much like a family. Also on the Course was one of the guys I had been through Marine recruit training with, David Ballard. Decades later I saw a ‘David Ballard’ on Facebook, so I sent him a message asking if he was the same person. He was, so we connected as Facebook friends. One of the first things David mentioned to me after we reconnected was that I had beaten him in the selection for who was to represent the Squad in the inter-squad boxing competition. Although we were both the same weight, David was bigger, more muscular, and more experienced than I was, so when I found myself up against him, I was expecting to get a pounding. I decided that I would go out fighting, so as soon as we got the go signal, I went at him with everything I had, knowing that David would just take my punches and then come back at me. Fortunately for me, the PTI stopped the fight before that could happen, so I ended up representing our squad at that weight. I knew that David was more deserving of the win, and I am sure that David knew it also, but he never said so, and that got him a lot of respect from me. It took over 50 years before I could say to him that I had won because the PTI stopped the fight, something which got me a “like” from him on Facebook. Some months later we were to meet up again and met for lunch. It was as though we had not seen each other for a few months instead of the 55 years plus; which goes to say a lot about a friendship. David Ballard and me in 2023

If you are wondering how I did in the Boxing Tournament incidentally; unfortunately, the referee didn’t stop the fight, and I took a pounding, as my opponent was an Amateur Boxing champion who went on to win the tournament at his weight. The Para Course was at RAF Abingdon and included personnel from all the Services, although the training was carried out by the RAF. Initially, we learned what was involved with embarking and exiting the aircraft, how to control the parachute in the air, how to handle our equipment, and how to land. Then we had eight jumps to make. The first two jumps were from a balloon and the rest were from an aircraft. The first four jumps were without equipment but after that we had to carry all our equipment, weighing 60+ pounds, on every jump. The final jump was made at night. We had trained to such an extent that the procedure for jumping was drilled into our heads. We knew exactly what was to happen and how we were to react. We had been trained that, as soon as the instructor tapped us on the shoulder and shouted “GO”, we were to jump out of the aircraft. On my first jump, we were in the cage suspended below the balloon. As we ascended to altitude, I ran through the procedure in my mind: As soon as I was tapped on the shoulder and heard the word “GO” shouted in my ear, I would launch myself from the cage. I was ready. But there was one slight problem: When we got to the desired height, instead of tapping me on the shoulder and shouting “GO”, the instructor said quietly, “Off you go then”. This was not the drill! So I shouted “GO” in my mind and dove from the doorway. Dropping from the balloon is a feeling I will always remember. Your stomach rushes up to your throat before the parachute opens and then you feel the tug of the straps on your shoulders and the sudden decrease in speed on your body, and relief in your entire being! You have the pleasant feeling of gently drifting towards the ground and then realise that you need to get prepared for your landing. Most people say that your second jump is the worst, as in the first one you don’t know what to expect, whereas in the second you do; I would agree with that. During the course, anyone may refuse to jump at any time, and nothing would be reported against them. We had only one person on our course who refused to jump. By the time we had made our jump and got back to our room, he was gone, having been returned to his unit. For me, the course went well, although on my last-but-one descent I had a bad exit from the plane. I was at the “end of the stick”, which meant that I had to run down the length of the plane to get to the exit door, and you didn’t have time to place yourself for a clean exit. When you are near the front of the stick, you can get out cleanly and, as soon as you get outside, the slipstream turns you and it is like flying along sitting in an armchair. Being at the rear of the stick, I wasn’t able to make a clean exit, so when I hit the slipstream of the aircraft I was thrown around a bit. When my parachute opened, I had gone through the lines, which meant I couldn’t control my direction or speed when I was coming into land. Consequently, I had a hard landing and injured my knee. At this point, I had only one more jump to complete the course. There was no way that I was NOT going to do the jump, as that would have disqualified me from getting my Parachute Wings. So, I went to the Sick Bay and asked them to bandage up my knee so that I could make my final jump. Their response was that if it was injured, I should not jump but come and see the doctor. On that note I walked out --- I would jump anyway. The evening of the jump I got a towel and cut it into strips and tied it tightly around my knee. I decided that when I exited the aircraft, I would pull my emergency parachute pull cord, working on the basis that if I had two parachutes open I would come down slower. As soon as I was out, and my main parachute had deployed I pulled my emergency cord. We had been told that, if at any time we weren’t happy with the way the jump was going, we should open the emergency chute. As soon as I pulled the cord, the emergency chute fell limp in front of me. “Shake it out number 5”, I heard from the instructor on the ground below. I shook the cords of the parachute, but it just still hung there. After a couple of minutes, I heard the instructor again: “Prepare for landing number 5”. It was then that I realised that I was close to landing, so I took up my position and hit the ground. I say hit the ground but really it was a gentle touch down. The conditions had been so calm and still that I just floated down. At least dealing with the emergency chute had taken my mind off the descent and I had completed my jumps with no problem. The instructor came up and asked what the problem had been. I replied that I just wasn’t happy and that was the last that was said. I collected both parachutes and my equipment, joined my fellow jumpers, and headed back to camp. After obtaining my Para Wings, I returned to 41, but Nat, my best friend in the troop, had been recruited by the Commando Recce (Reconnaissance) Troop, as he had served with Recce Troop in 42 Commando in Singapore. He recommended me, so I was invited for an interview with the Troop Commander and Troop Sergeant, after which I was asked to join them. Recce Troop is the eyes and ears of the commando. It works in small teams, gathering information from behind enemy lines. It means being self-sufficient and being able to blend into the background. Consequently, you need to be able to work as an individual but also as a member of a team. Despite having changed to Recce Troop, I remained friends with a number of the guys from F company and still have contact with a couple of them, including George Hearn. On one occasion, we were about to go off for a day’s training and the troop sergeant was calling out who was to be on duty that weekend. When he called out George’s name, there came a shocked response of “I can’t be on duty this weekend Sarg, I’m getting married Saturday.” “That’s a good excuse” came the reply. With some of my friends getting married, I found that I was getting invited around to dinner quite a lot. I think one of the reasons for that was because I would eat anything and, what’s more, I would enjoy it and compliment their wives on a great meal. Later, I developed a saying that I frequently use to this day: “You put it on the plate, I’ll eat it.” Stuart Edinburgh, another of my friends from F Company, received a posting to HMS Intrepid very shortly after getting married and, needless to say, he wasn’t happy about it. A great benefit of the Marines is that, if you get a posting and don’t want it, you can find someone else to take it for you. I offered to take the posting for Stuart so he could enjoy married life with his new wife. Now I was off on a new adventure, setting sail around the world. Chapter 5 - Service with Royal Navy |

|

|

|

|

| Site Map |