|

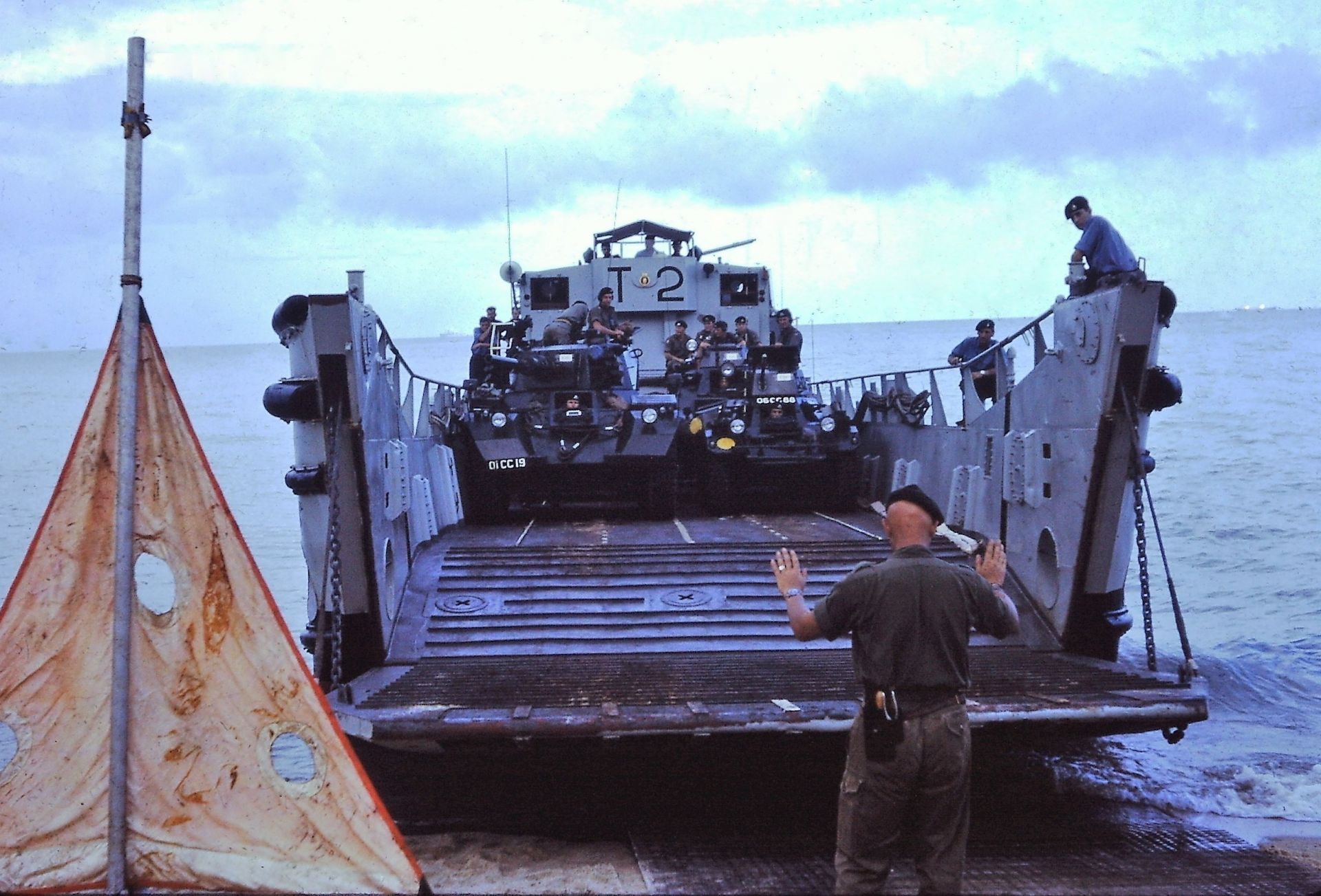

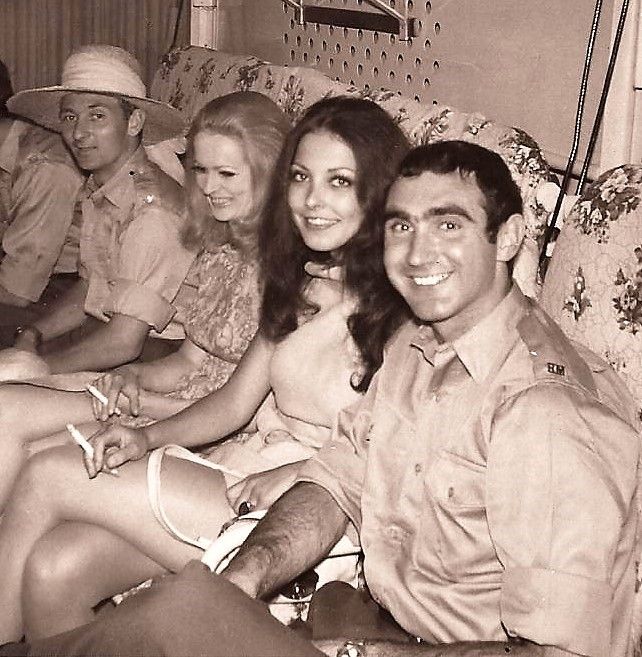

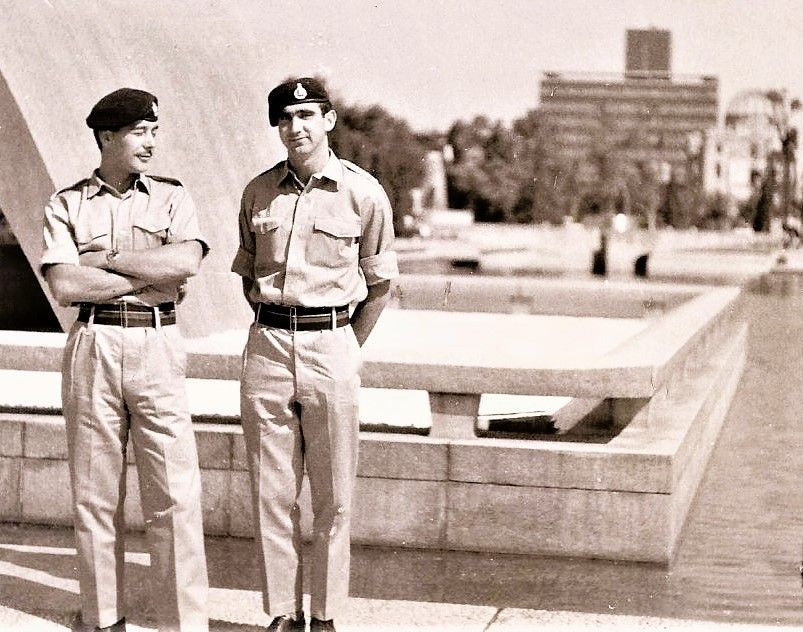

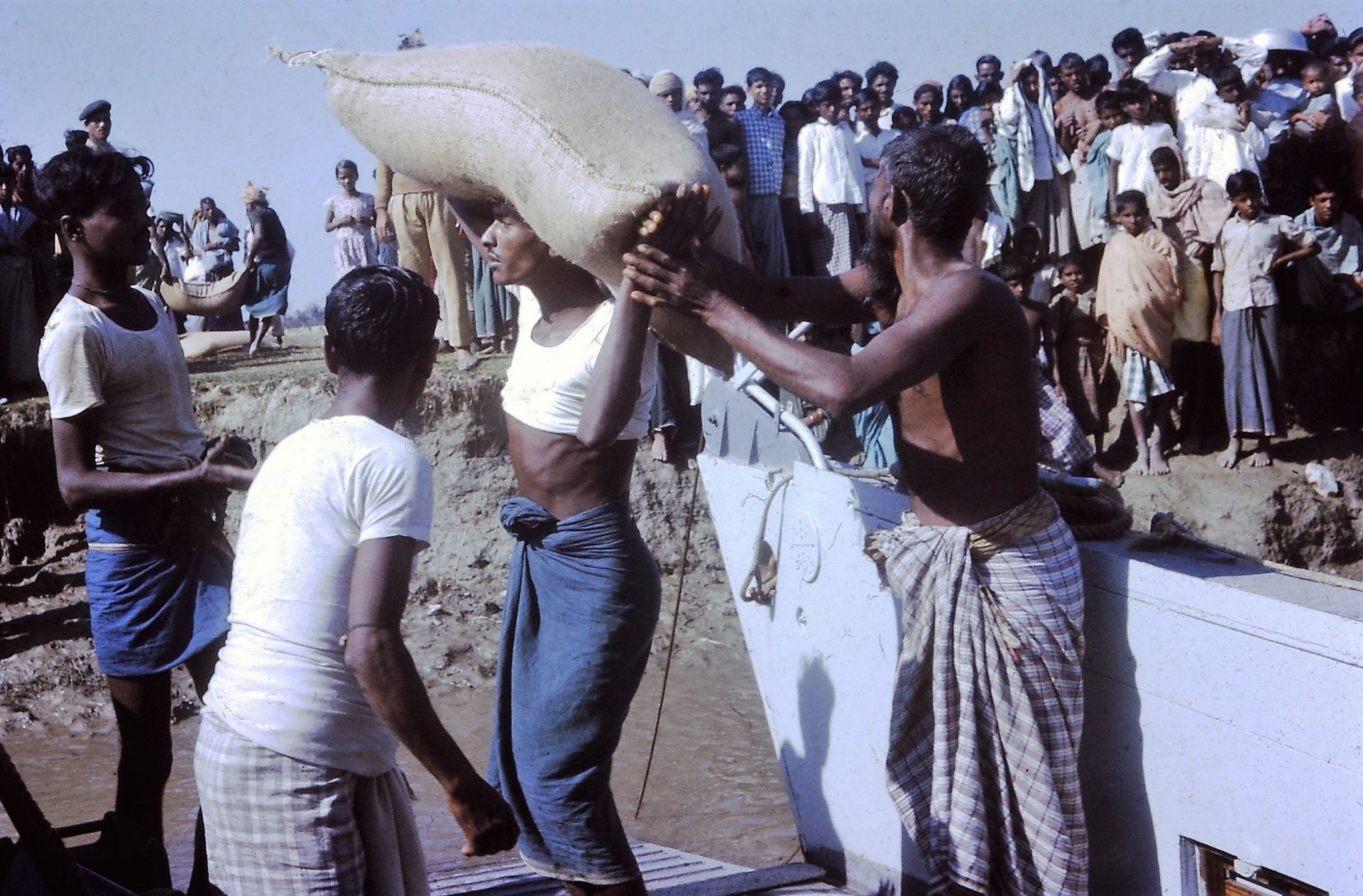

Service with the Royal Navy Prior to taking up my posting on HMS Intrepid, I was required to undergo amphibious training in Poole, Dorset. During a Marine’s initial training, they are taught basic amphibious procedures, spending two weeks learning such things as how to carry out a beach assault from landing craft. They are also introduced to the use of light raiding craft, such as the Gemini, a mobile and versatile type of inflatable boat that can carry five Marines, plus the driver, at a speed of 20 knots. This basic training was simply how to get in and out of each type of craft, rather than learning how each craft worked or the procedures involved. My later training in Poole was more specific to the Marines’ roles on HMS Intrepid and went into much greater depth than the basic course. We had to learn how to lower and raise the ramp, how to manoeuvre alongside the ship or a pier, and numerous other skills related to seamanship and amphibious warfare. It was during this training that I met James Shanks, who was to become a lifelong friend. He and I spent many hours on Intrepid's forecastle, drinking our mug of tea after dinner each evening. James was Irish and Protestant while my other close friend on Intrepid, Bernie McKeon, was Irish and Catholic. The three of us became good friends during a period when The Troubles in Northern Ireland were at their height. The religious differences between James and Bernie were never an issue for the three of us. It was only when the time came for Bernie to get married, and James was not allowed to attend because the guest list was determined by religion, that the stark reality of what was going on in Ireland truly presented itself to us. Since I had been confirmed in the Catholic Church, I not only attended the wedding in Northern Ireland but was Bernie’s best man as well. One great result of that wedding (aside from Bernie’s marriage) was my realisation that I had a real aptitude for public speaking. While getting up to speak in front of all those guests brought me many compliments, it also made me realise how easy it was for me to stand up and talk in front of large crowds – something that I would use to my advantage in later life. In December 1968, having finished our amphibious training, we flew to Singapore to join the ship. HMS Intrepid was an assault ship, designed to operate landing craft and helicopters, as well as provide a headquarters for amphibious forces and their heavy armour. It had a length of 520 feet, a beam of 80 feet and a displacement of 12,160 tons. The ship was built with a tailgate that could be lowered in order to flood its dock, allowing the landing craft to sail into the body of the ship. Once the craft were in, the tailgate was raised, the water was pumped out, and the craft would settle onto the deck, making Intrepid ready for sailing.  The ship’s company consisted of 42 officers and 520 men, which were not only Royal Navy and Royal Marines but also Army personnel. The Marines were part of the Amphibious Detachment whose job was to move the embarked troops - the term used to describe any force that we were required to transport - and get them from the ship to the beach and then safely off the beach inland. To do that, we were split into three units. The first two were Landing Craft Squadrons, one which manned the small LCVPs which transported personnel or land rovers, and the second which manned the larger LCM or Mk 9’s, which transported larger vehicles like 3 tonners and tanks. The third unit, the Amphibious Beach Party, was responsible for laying the tracks on the beach upon which the vehicles were driven, and for then getting the troops, vehicles, and equipment off the beach as quickly as possible. I worked with each of these units during my time on Intrepid. In addition, there was another unit of the Amphibious Detachment, which was the Vehicle Deck Party, which was manned by Army personnel, who remained on board the ship and loaded the men, vehicles, and stores into the landing craft for transport to the beach.  The crew of the LCVP (Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel). Me in the centre of the photo. As soon as we joined the ship, we were assigned to one of these units. I was put with the Amphibious Beach Party, learning exactly what was required of me and how I would carry out those requirements. Once we had learned the theory, we would put our knowledge into practice by going on exercises to prove that we could do what was required. Initially, that was just carrying out the drills ourselves, but once we had mastered them, we would embark other troops and get them ashore. We did these exercises in places such as Malaya and Borneo. I got a kick out of sitting on the beach in some exotic land, watching the sun go down, and wondering what the people back in England were doing. When not at sea or on exercise, we were able to go ashore to visit some of those exotic places. The ship was based in Singapore, where we had some great “runs ashore”, but we also travelled to other places in that part of the world, providing us with opportunities for some great trips out.  It didn’t take long for us to settle into the ship’s routine, which meant getting to know our way around and becoming familiar with our duties. We also had to learn our “action stations” - which is where we had to go in the event of an emergency. We were drilled until the proper response became second nature to us. One of the greatest dangers on a ship is that of a fire, and we would regularly practice to prepare for such an eventuality. Our accommodations on Intrepid were far from luxurious. There were 30 men in our “mess”, which served as both our living and sleeping accommodation. The bunk beds are stowed away during the day, to be pulled down at night to provide a 3-tier sleeping arrangement. I had a top bunk, which was fine, but it was right next to the ventilation duct, so a bit noisy. I remember thinking that first night, “What have I let myself in for here!” One of the guys, prior to joining the Marines, had been a farmer. He informed us that if we had wanted to keep pigs in the same amount of space that we had for our mess, the maximum number of animals that could be accommodated would be ten. There were 30 of us! Living in such a tight space meant that we had to adapt to living in very close proximity to each other. Coming to terms with our cramped living conditions taught me that one of the most helpful assets you can have in life is the ability to get along with other people. This was something I later adapted to life in general. I’ve found that being nice to people, regardless of their position, and treating them with respect, generally means that they will reciprocate in kind. One thing I could not fault on Intrepid was the food. The ship’s catering staff was Chinese, recruited from Hong Kong. In those days, I bore a resemblance to actor Sean Connery, when James Bond films were very popular, particularly in Hong Kong. So, the cooks all called me James Bond, something I must confess I milked a bit --- well, I remembered the discus throwing corporal’s lessons from Aden about the importance of getting on with the chefs! One of our most frequent tasks onboard was chipping off old paint and repainting where necessary. The ship had sailed many thousands of miles in the two years of its first commission and was now well into its second commission. A number of needed repairs had come to light, so Intrepid was ready for a refit - a major overhaul - and for that, it needed to go back to the UK. At this time, we had been away for six months, and the married guys particularly were looking forward to returning home. Although, most of the single guys were also happy to return, as we would be taking the ship back around South Africa, where we would be calling in at many interesting places on route. One of our ports of call in South Africa was Durban. I decided to have a walk ashore and look around. We were required to be in uniform and, while walking along a street, a man approached me and struck up a conversation. He asked if I would like to go and visit the Zulu Reserve. I must have given him a funny look as he said that he was with his family in the car, which he pointed out, and they were going to see it and wondered if seeing as I was on my own, I would like to come too. Quickly sizing up the situation and liking the look of his family, I accepted. He was a senior policeman in Durban and had with him his wife, daughter and son-in-law, and their baby. All welcomed me as an old friend. We drove the one-and-a-half-hour journey to the Valley of a Thousand Hills. This is an area of magnificent scenery, as well as a living museum of Zulu life, complete with ritual dance displays. After the visit, I was invited back to their home for dinner, after which they drove me back to the ship, offering me accommodation if ever I found myself back in Durban. When you think of places, generally, the thing that makes the place memorable are the people that you meet there, so I liked Durban. In the years to follow when I was travelling, I would often travel on my own and found it a great way to meet people. If you are friendly and sociable, people will always talk to you and welcome you into their group. I’ve met many interesting people simply because I was on my own. When we crossed the Equator on our way back to Britain for our refit, we had a ceremony on board for those who hadn’t previously “Crossed the Line.” This was an initiation into “King Neptune’s Court.” Some of the guys took on the roles of the members of the Court. King Neptune himself presided over the ceremony. His ‘police’ were charged with bringing all the “initiates” to a pool that had been erected on the flight deck. Each was initiated by being dunked in the pool.  Many years later, when speaking on a cruise ship, I received an official certificate confirming that I had crossed the line when that ship went across the Equator. That was nice but the ceremony on Intrepid was certainly more memorable! Upon our arrival back in England, Intrepid docked at HM Dockyard Devonport in Plymouth. At that time, I had been moved to Landing Craft and was a crewman on the LCM/Mk 9’s. We were to take the craft to the Amphibious Training Centre at Poole and carry out more training there. At that time, I had never driven a car, and I wanted to do a driver’s course - well I wanted to learn to drive and get a driving licence. So, I got myself detached from Intrepid to 41 Commando, and, once there, I called into the Motor Transport Section and explained that I was on detachment from Intrepid and could I get on a Driving Course, justifying my need as a standby driver for the captain. The following morning, I was informed that I had been booked on a course at Lympstone starting the next week. The good thing about military driving lessons is that you are unlikely to be put in for your test if the instructor does not feel that you will pass, so when I took the test, I was quietly confident that I would pass, and I did. However, when my unit on Intrepid was informed that I had successfully completed the course, they didn’t know anything about it! As I had failed to go through the “proper channels”, they were none too pleased. I was recalled to the ship. Now, since I had my driving licence, I decided to buy myself a car, as Intrepid’s refit was to take a whole year. I had been going up to Birmingham most weekends to visit Celia (Stuart Edinburgh’s wife’s attractive sister, whom I was dating at that time) which was a 200-mile trip, so I bought myself my first car, a second-hand Mini Cooper. One weekend in Birmingham, my car wheel hit a large pothole and I was concerned about driving all the way back to Plymouth that night. I called into the police station and asked them to notify HM Dockyard that I had had a car accident and that I would be getting the train down in the morning. My leave was to expire at 8:00 a.m., and I knew I couldn’t make it back before then. However, when I got to Plymouth the next morning, I discovered that my message hadn’t been passed through to the ship. The Sergeant Major charged me with being Absent Without Leave. Eventually, it was discovered that the message had got to the Dockyard as I had requested but hadn’t been passed on to the ship. Despite this, the Sergeant Major decided that, because there had been a train in the very early hours of the morning, I should have caught that one instead of the one I did, so he let the charge stand. Being extremely unhappy at this unfairness, I proceeded to tell him exactly what I thought of him in no uncertain terms, and that I wouldn’t be obeying any future orders that he gave me. This resulted in an additional charge of Failing to Obey an Order, which resulted in me being incarcerated for 21 days in the Naval Detention Quarters. I learnt a lot in those 21 days in the Detention Quarters. I wouldn’t have missed them, but to tell them all would be another book in itself! The time in detention shaped my whole attitude to life. I got used to my own company, as most of my time was spent locked in a cell by myself. I learnt to live with being alone and accept it. Time outside my cell was spent either doing drill or PT - no socializing allowed. Three weeks later when I returned to the ship, we had a new Sergeant Major. The old one was moved on, as he should never have charged me “Absent Without Leave” and everyone knew it. Many years later, when I was giving talks on cruise ships, a guy came up to me after one of my talks and told me that he was one of the escorts who took me to the cells after my remonstration with the Sergeant Major. There were two books available to me in Detention: the Bible and "Paddle your own Canoe" by Robert Baden-Powell, which is a true roadmap to life. It was excellent and an ideal book to read in that situation. It is one of the books I would recommend to anyone. There are several pieces of literature that have influenced me over the years and that was one. Two poems that have also meant a lot to me are "Desiderata" by Max Ehrmann and "If" by Rudyard Kipling, which was to become my philosophy on life. After those 21 days in detention, I returned to Intrepid and was given the opportunity to either stay on the ship or be posted elsewhere. I chose to stay and soon became involved in many of the ship’s activities. I became the Amphibious Detachment’s representative on the Ship's Committee and joined the ship’s choir. Although I didn’t go to the religious services, I did enjoy discussions with the chaplain. I joined him for several outings, including visits to the home of the Franciscan Friars at Cerne Abbas and, once abroad again, to a hospital for lepers and a Buddhist monastery in Hong Kong. One fun thing that I did was to write to “Pan’s People”, a group of five extremely popular “go-go” dancing girls from the UK’s hit TV show “Top of the Pops”, asking if they would be our Mess Mascots. We were delighted when the girls agreed and sent us some autographed photographs. We boldly invited them to visit us on Intrepid. As a result, several of us from the Mess were invited to attend a studio recording of the TV show. Afterward, the girls came to Intrepid with a film crew and filmed a dance sequence on the ship’s deck, which was shown on Top of the Pops. The girls stayed overnight, and we ended the day with a very pleasant dinner. I was asked to write an article for the “Globe & Laurel”, the Royal Marines magazine, about the Pan’s People visit, which I duly did. That was to be my first published article.  The refit of Intrepid was finished and we set sail back to Singapore. We again called in at South Africa, but this time in Cape Town. This time, however, my run ashore was less cultural than my day in Durban with the policeman and his family had been. Once again, we were required to wear our uniform while ashore. One of the guys had gotten involved with a local nurse and they were having a party. She asked if he would bring some of his shipmates. A few of us were quite happy to go and do our bit for British/South African relations, but we were reluctant to be at the party in uniform. We put together a plan. We would go ashore in uniform but take our civilian clothes in a bag. We would then stop in at the railway station and change out of our uniforms and leave them in our bags in the “Left Luggage” at the station. The night of the party came, and our strategy worked perfectly. After the party ended, we returned to the train station and changed back into our uniforms before returning to the ship. It was quite late, and I reasoned that there wouldn’t be many people around on the ship to see us return, and decided not to take the time to change into my uniform shirt. So, although I was in uniform, instead of having my khaki shirt on, I had on a pink one. When we returned to the ship, who should be at the top of the gangway but one of our officers. He enquired if we had had a good night and we said that we had, followed by a few pleasantries about our evening. As we turned to go, he called after me; “By the way Gatepain, next time, change the shirt”. “Yes sir”, I responded meekly, like a child having been caught with his fingers in the sweets jar. Nothing more was ever said. There were three Marine officers on board, a Major who was in command of the Amphibious Detachment; a Captain who was responsible for the Vehicle Deck and embarking and disembarking all vehicles from the ship, (his name tag had him as VD Officer, which always got a few laughs), and a Lieutenant who commanded the marines on board and so was in charge of us. His name was Tim Borne, and it was he who met us at the gangway when I was wearing the pink shirt. Many years later, when I was giving a presentation to the Rotary Club about the Reserve Forces, someone came up to me following my talk and mentioned that his next-door neighbour’s son had been a Marine. I asked about when he was in, which coincided with the time I served, so I asked his name. It was Tim Borne. I asked the man to pass on my regards and tell him that I had reached Lieutenant Colonel, which I was sure would surprise him after my experiences on Intrepid! Once back in the Far East, an important part of our tour duty was “Showing the Flag”. This was an effort to create “goodwill” towards the British and its Armed Forces in other countries around the world. My friend James was the Captain’s driver, so, whenever the ship docked in port, James would go ashore and drive around, familiarising himself with the area. He’d take me along with him, so in effect, I had my own personal chauffeur. In this way, I got to see a lot of things that I wouldn’t otherwise have seen. Of the many places we visited, several stand out in my memory. I loved the bustling, vibrant atmosphere of Hong Kong where we had the chance to look around the shops. You could buy expensive items for a fraction of the price back home. Then there was the Po Lin Buddhist monastery on the island of Lantau off Hong Kong. The visit was arranged by the ship’s chaplain and entailed a boat ride from Hong Kong to the island and then a coach ride to the centre of the island where the monastery is situated. That coach ride is the most hair-raising journey I have ever made in my life. The road was extremely narrow with no room for vehicles to pass. It had a cliff face on one side and a shear drop on the other. That alone would have made most people nervous, but the driver just put his foot down on the accelerator and went for it. I had done abseiling, parachuting, and rock climbing and I was still nervous! I thought about sitting on the floor, but I didn’t want to blow my image. I looked across at my companions and I could tell by the looks on their faces that they were as nervous as I was. I held on to the seat in front of me trying to look nonchalant and eventually, we arrived safely at the monastery, fortunately without meeting anyone coming in the opposite direction. The monastery was a beautiful complex. I thought of it again when, many years later, I visited the Forbidden City in Beijing, as its architecture was similar. On entry, we were met by one of the monks who took us into the large hall with its beautiful bronze statues of the Buddha, representing his past, present, and future. He then took us to the room which we were all to share for the night. Mosquito nets hung over each of the beds. We dropped off our overnight bags and had a look around. We knew that there wouldn’t be anything to do after dark, so we resolved to have an early night. We enjoyed a leisurely meal and then headed for bed. Before I got into my bed, I spent a good ten minutes looking for any mosquitos and ensuring my mosquito net was tightly closed around my bed. This got a bunch of snide remarks from the other guys who jumped straight into their beds without fixing the net. But I remembered my visits to France with my mother and Rose-Marie and how mosquitos seemed to really like me. Eventually, content that I was sleeping alone, I got into bed and quickly nodded off. The next morning, we awoke at sunrise and went to the large hall for breakfast. In time we were joined by the monk who had met us the day before and he took us on a quick tour of the place, telling us its history and explaining about their way of life and their religion. It fascinated me and was the foundation of my interest in Buddhism and many other world religions. All too soon, it was time for us to leave and that was something we weren’t looking forward to, not the leaving, but the perilous coach journey back across the island. The journey back was just as hair-raising, although once again we met nothing on the road. One funny thing I did notice on the return journey was that all the other guys were scratching themselves continuously. “Oh…Did you get bitten by mosquitos?” I asked. “I didn’t", I added with a snigger. Another memorable visit on our travels was to Hiroshima, Japan. It was an official visit, so we were welcomed by a civic party, complete with a band. We were all keen to get ashore. James, as the Captain’s driver, needed to get off as soon as we docked to drive around and get his bearings, so I went with him. One place that we noted was the Peace Memorial Park, which is located at the epicentre of the atomic blast that devastated the city on August 6th, 1945. There was a museum and several monuments dedicated to those killed by the explosion. James and I resolved to return later to look around. When we returned, we had just started to walk around the park when we were approached by two young students. We were in uniform and they were learning English so wanted to engage with us. Consequently, we had our own personal guides to explain about the monuments and the traditions attached to them. They told us about the Children’s Peace Monument and about a 12-year-old girl who had died of leukaemia 10 years after the bombing. She had made paper cranes, the Japanese symbol of longevity and happiness, prior to her death in the hope of being cured. They explained about the Atomic Bomb Dome, which was one of the few buildings not totally destroyed by the blast. We saw the Cenotaph, inscribed with the names of all those who lost their lives, the Peace Bell, and the Flame of Peace, which burns continually until the abolishment of all nuclear weapons takes place.  After looking around the park, James and I went inside the Museum. The displays included belongings left by the victims, coins that had been fused together by the heat, photographs of the people and their injuries, and the human-shaped shadow on the pavement made by someone who was standing there during the flash. All these things conveyed the horror of the event. Certainly, visiting the Peace Museum brought a touch of reality to the lives of two young Marines who left the building with a lump in their throats. This experience was to resonate on other occasions later in my life when I visited places such as the War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; the former Nazi Concentration and Extermination camps of Auschwitz and Birkenau in Poland, and the 9/11 Memorial and Museum which stand on the site of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre in New York. Back on Intrepid, it wasn’t all smooth sailing. Because it was a flat-bottomed ship with no stabilisers, when the sea had a bit of a swell, the ship would be tossed around quite a bit. You can imagine what it would be like in a force-nine gale, and we had one of those in the Indian Ocean. I was fortunate as I was a reasonably good sailor and didn’t suffer from sea sickness, but some of the guys did have a problem and had to retreat to their bunks. It was at times like that, that members of the ship's company were able to obtain an extra ration of the “tot” in exchange for doing someone else's duty. I should explain what the tot was: This was a ration of rum that was given on Royal Navy ships each day at mid-day. This custom existed between 1850 until it was abolished in 1970, much to the disappointment of Naval personnel. I know this from personal experience as I was on Intrepid at the last issue of the tot. The tot for Junior ranks consisted of one part rum and two parts water. Those who didn’t drink would receive a few pence a day extra. Although I didn’t drink rum, I did claim my ration, as on board it could be used like currency, and if you wanted someone to do something for you, you would invite them around to your mess for your rum ration. One incident that certainly wasn’t smooth sailing occurred when we were on exercise in Borneo. We were traveling along one of its rivers when our LCVP landing craft hit an underwater branch that pieced its hull. We immediately took on water in the area that held the troops. Fortunately, we were with other craft, so one of them came alongside us and we were able to tie ourselves together which prevented us from sinking. We tried to pump out the water but that was ineffective because we were stuck on the branch and we couldn’t move it, so we were going nowhere. The only way out of our problem was to call for help from Intrepid, and that help required a diver to saw off the branch from below the craft. The incident occurred late in the afternoon. We never got any sleep that night.  The next morning the branch had been removed and a temporary patch placed over the hole, so we were able to limp back to Intrepid. As dawn broke and the sun rose, the sky was one of the most beautiful that I had ever seen, which made the whole night worthwhile. One experience that was truly life-changing for me came during my time onboard Intrepid. In November 1970, when everyone was excitedly looking forward to setting sail to Australia, we learned that the trip had been cancelled. The devastating Bhola cyclone had hit the Ganges Delta in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), and HMS Intrepid was being sent to assist in relief operations instead. The cyclone struck on November 11th, 1970, and it remains the deadliest tropical cyclone ever recorded and one of the world's deadliest natural disasters. At least 500,000 people lost their lives in the storm, primarily as a result of the storm surge and tidal wave that flooded much of the low-lying islands of the Ganges Delta. Our job was to take supplies by landing craft to those islands. Our landing crafts were ideal for this as, being flat-bottomed, they could navigate in shallow water and get right up to the land, yet they could carry a considerable number of stores. They also had the benefit of being able to lower the ramp at the front of the craft, which meant that people could walk on and carry the stores off easily.  The British aid naval response consisted of HMS Intrepid, HMS Triumph, HMS Hydra, and the Landing Ship Logistics (LSL) Sir Galahad. Because of their draft, the closest that these ships could get to shore was 35 miles, and it was a further 40 miles to the main supply dump and headquarters, which meant that all our craft and personnel would have to be detached and work permanently ashore. We took four LCMs, four LCVPs, two naval store tenders, two Launchers, 15 Assault boats, and 10 Geminis. I was on one of the LCVPs. Leaving Intrepid, we had hoped to get to our location by nightfall, but due to the sand bars and mud flats, progress proved difficult, so it was decided that we would anchor for the night. It was then that the seriousness of the situation hit us as we inhaled the smell of rotting flesh from all of the carcasses and bodies of the dead. We had our meal but there wasn’t the normal jovial conversation. Ken Murgatroyd was our coxswain, and he drew up a watch list and we found a spot amongst the stores for our beds. I closed my eyes to try to get some sleep as the silence and the smell intensified. The next morning, after a very uncomfortable night, we reached our destination, where we stayed for nine days. Each morning we were loaded with relief goods and then headed off under the supervision of a Pakistani soldier and a guide to deliver the supplies, and then return each night. Despite the long hours we worked and the harsh conditions, I never heard anyone complain. There were television news crews with us, and I remember thinking that I hope this will make people in the UK realise how fortunate we are there. What I witnessed in Bangladesh made me appreciate the many comforts and privileges that we often take for granted. For, in addition to the lives lost in the disaster, there were ongoing and long-term ramifications for the people of the region. In the best of times, these people eked out a meagre living as small-scale farmers and fishermen. Now, their homes and fishing boats had been destroyed, and most of their cattle, sheep, and goats had been killed. The rice crop was ruined. We knew that whatever we could do to help was not a quick fix but was only going to keep them alive temporarily. It was a monumental experience for me and one that I have never forgotten. While in the Delta, I wrote a poem, Ode to the Ganges Delta, which epitomised my feelings. This was also published in The Globe & Laurel. by Marine Ron Gatepain To sail the Ganges Delta Today’s no pretty sight For no matter where you wander There are bodies left and right. Floating in the water Lying on the bank Face up in a rice field Stretched out on the track. The smell of death around you You have to wonder why What caused this move of nature To make these people die. You have no time to ponder For there’s a job to do To take food to survivors To help to see them through. To take them warmth and shelter A glimmering of hope To help them face the future And enable them to cope. A body floats on by you You glance then turn away For that was like yourself once Where now it’s part decay. You must have time to wonder A little time to think Though make it when their water’s through And they’ve had a chance to drink. Survivors rush to meet you With such a hopeful stare A look that seems to cry to you I’ve come to beg my share. The sun descends so quickly And night then fills the air The moon it spreads a silver veil Of glimmer everywhere. Left alone just with your thoughts The world now seems so still Not like the day that nature sent Her waters in to kill. Following the completion of the relief operations, we returned to Singapore and got back to our normal routine. December 1971 marked the end of Intrepid’s second commission and our time on the ship. Prior to completing its tour, two of us were asked to produce a book, which would be given to all of those who had served on the ship during that commission. It was a memento of where we had been and what we had done. That was my first editing job. A few days before I left the ship, I was told that the officer in charge of the Amphibious Detachment wanted to see me in his office. While waiting to go in, I was trying hard to think of what I might have done wrong now. When I got there, however, he told me that he had been quite worried that I might give him problems after my return from the Detention Quarters, and he wanted to thank me, as my behaviour had been exemplary. Chapter 6 - Return to Civilian Life |

|

|

|

|

| Site Map |